Kalig Coral Research Station – Indonesia

Please enjoy this video about Seahawk’s visit to the Kalig Coral Research Station in December 2024.

A Personal Reflection

I am thrilled to be making my first contribution to the Seahawk Mission Logs, and this entry is especially close to my heart.

To introduce myself, I am Sarah, and I work as the Second Stewardess aboard Seahawk. My connection to the ocean runs deep, but it truly began in 2014 when I moved to Australia and experienced my first dive on the Great Barrier Reef, not far from Airlie Beach. It was nothing short of magical. The coral was bursting with colour, and shimmering schools of fish surrounded me. If I told you I felt like I’d been transported into King Triton’s kingdom from The Little Mermaid, it wouldn’t be far from the truth.

But the reality of our changing oceans hit me just a year later. I returned to Airlie Beach to work on a dive vessel, same place, same waters, but a very different underwater landscape. Much of the reef was bleached and broken. There were still pockets of beauty, but large sections reminded me more of the Elephant Graveyard from The Lion King than the vibrant world I had first fallen in love with. (Yes, I’m a passionate diver and Disney enthusiast.)

That moment, ten years ago to the day, was when I truly understood how fragile these underwater ecosystems are, and how quickly they can change.

Which is why I am so proud to share this next chapter: SY Seahawk’s visit to Kalig Reef Station, a project at the forefront of coral research. The work being done here is pioneering. It’s focused on understanding coral resilience in the face of rising ocean temperatures, something that feels deeply personal to me and is urgently necessary for all of us who care about the ocean’s future.

At the Heart of Coral Conservation: Kalig Reef Station

On December 7th, 2024, we arrived at Kalig Reef Station aboard SY Seahawk, deep within the Misool Marine Reserve in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Raja Ampat is one of the most colourful and diverse underwater places on Earth, home to approximately 75% of the world’s coral species. Walking into this remote research station felt like a small piece of paradise, and we couldn’t wait to learn about the important work being done here and lend our assistance.

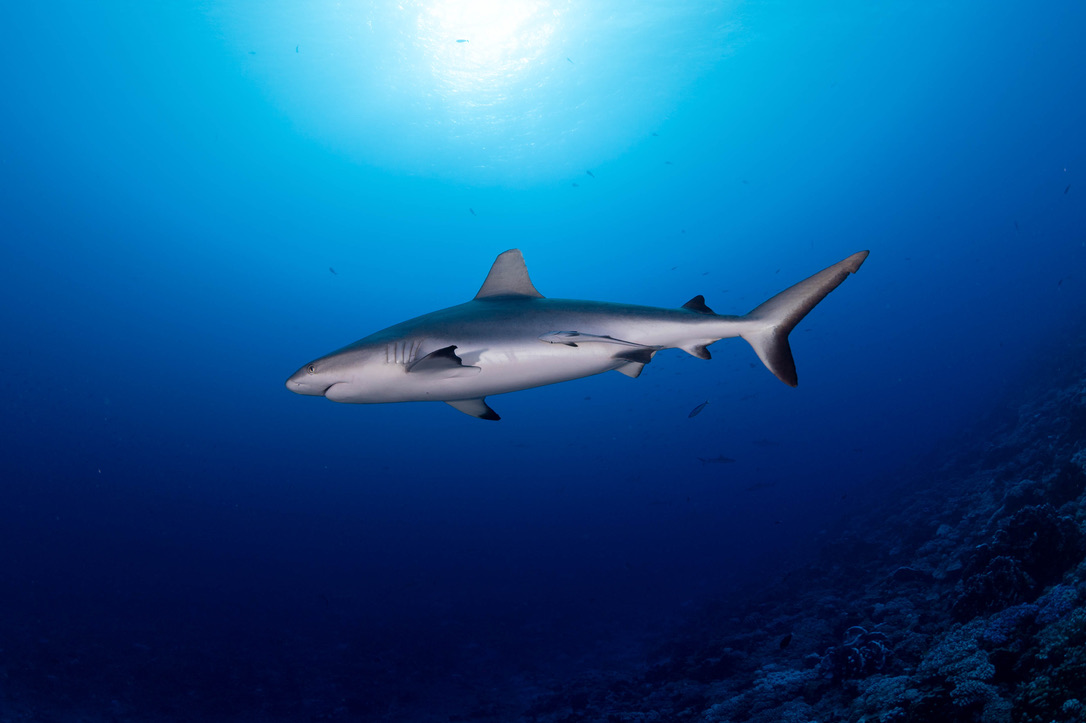

Kalig is run by the Misool Foundation, Indonesia’s only marine conservation group dedicated to saving these incredible reefs. The vibrant coral here supports an amazing array of marine life, from graceful manta rays and reef sharks to sparkling schools of fish that swirl like living rainbows.

The sheer biodiversity in these waters makes them a critical stronghold for global reef conservation. What is learned in Raja Ampat could inform coral protection strategies for threatened reefs all over the world.

Why Coral Matters, and Why It’s in Danger

You can identify healthy coral as it is full of tiny algae that give it energy and bright colours. When the water becomes too warm, coral becomes stressed and expels the algae, turning pale or white, a warning sign known as bleaching. If the heat keeps up, the coral can die, and with it, the entire reef ecosystem suffers.

These algae, called zooxanthellae, are not just passengers; they are essential partners in coral survival. Through photosynthesis, they provide up to 90% of the energy that corals need to grow and build reefs. When coral loses them, it’s like pulling the plug on a life-support system.

Seeing this fragile process up close was heartbreaking. Coral isn’t just a beautiful part of the ocean; it is the ocean’s foundation. Without it, countless marine creatures lose their homes and food. The work being done at Kalig Reef Station is crucial for giving coral reefs a fighting chance.

The Coral Resilience Trials: Hope in Science

Our visit centred on a groundbreaking project known as the Coral Resilience Trials. Scientists here are working to find out which types of coral can survive warmer ocean temperatures, a question that could determine the future of coral reefs worldwide.

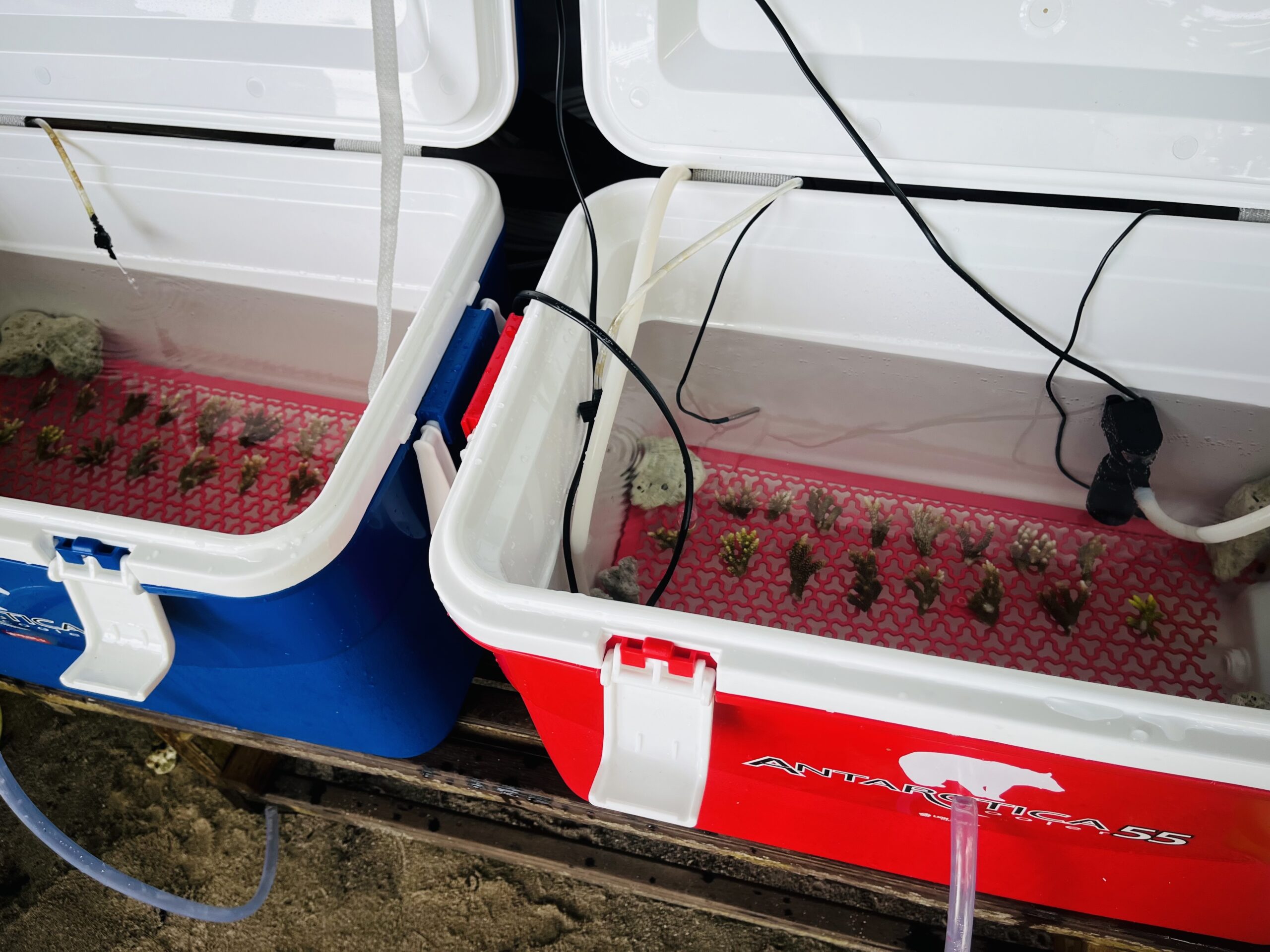

We had the privilege of joining an inspiring team of scientists, including Jaka Fadli and Dzikra Fauzia. To help test coral resilience under controlled conditions, the guests and crew

from Seahawk assisted in the careful collection of coral samples. Two small fragments were taken from the same colony using garden shears, cut low enough on the branch to allow for replanting later. Back at the station, one fragment was placed in a tank set to match its natural ocean temperature. In contrast, the other was placed in a tank where the temperature was gradually increased by one degree Celsius each day, mimicking the heat stress corals may face in the warming oceans of the future.

This controlled trial setup allows researchers to isolate genetic differences in heat tolerance. Some corals bleach within days, while others retain their colour much longer, potentially indicating naturally heat-resistant strains that could be key to reef recovery in a warming climate.

By observing when the coral begins to bleach, turning white as it expels the algae it depends on, scientists can identify which individuals are more tolerant to rising temperatures. These insights help us understand which corals are best equipped to survive in a warming world.

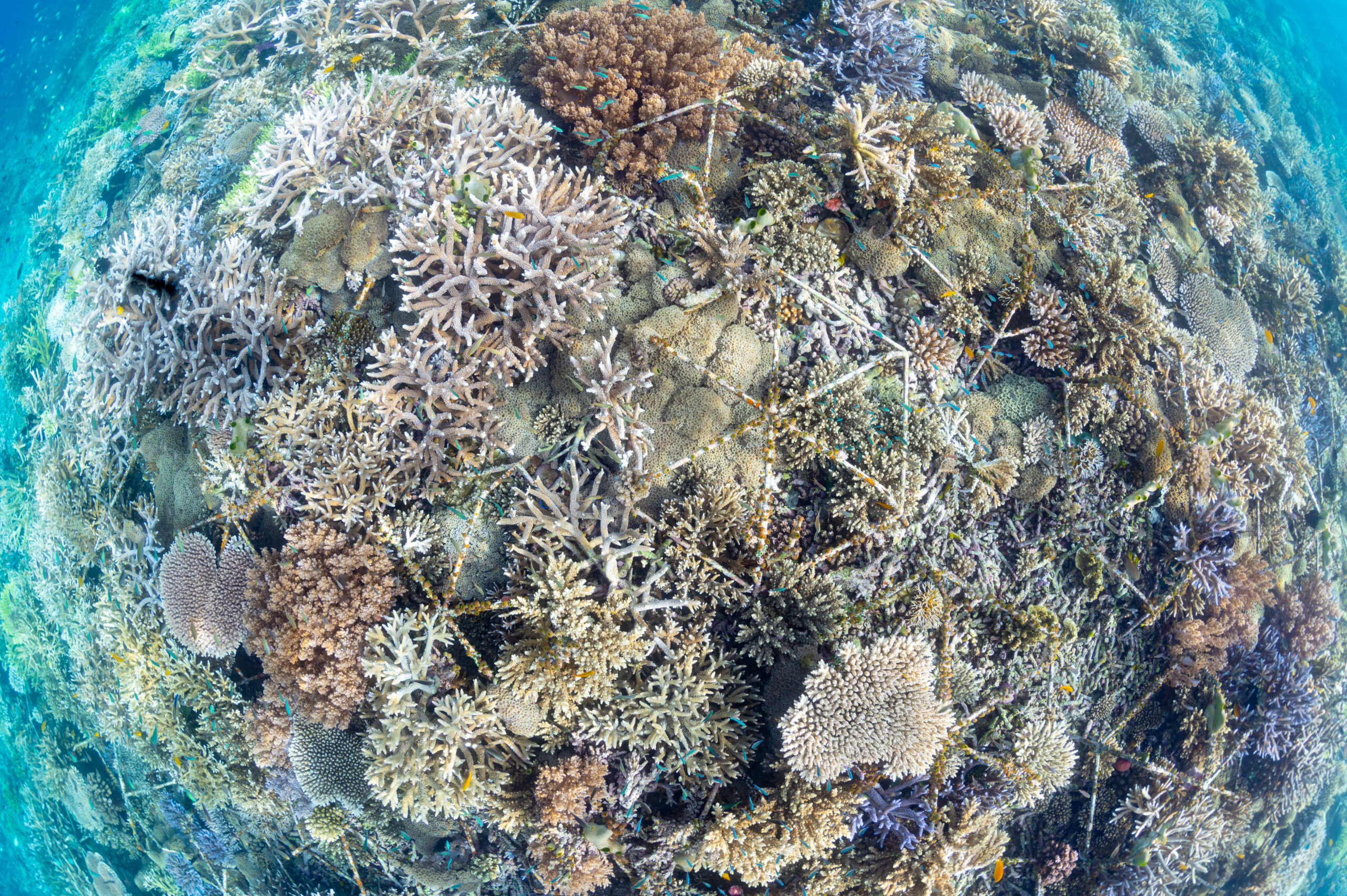

Helping Reefs Heal: Reef Stars

To support coral growth, the team also uses special hexagonal steel frames called Reef Stars. These act like underwater scaffolding, helping broken coral pieces attach and grow back strong. Over time, these “reef spiders” help rebuild damaged areas faster, giving the reef a chance to recover.

Made from marine-grade rebar coated in sand, these structures are designed to mimic the natural reef typography, stabilising loose rubble and increasing coral survival rates. Field studies have shown that coral growth on Reef Stars can reach 25 cm per year, an impressive rate in reef terms.

A Personal Call to Action

One moment stayed with me: the realisation that fish can swim away from warmer waters, but coral can’t. It is fixed in place, vulnerable, and absolutely vital to ocean life.

This work isn’t just science, it is a survival plan. As we sailed away from Kalig, I felt a deep responsibility to share this story. Protecting coral reefs means protecting the oceans we all depend on.

If we want vibrant, thriving oceans for future generations, it starts with understanding and caring for coral today. Conservation isn’t just about saving something beautiful; it’s about saving life itself.

Written by Sarah Thrower

2nd Stewardess