Galapagos – Sailing and Swimming Program

We cannot live only for ourselves. A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men. – Helman Melville

As we sail away, reaching new horizons, we remember the days spent in the Ecuadorian islands of San Cristobal, Isabella, and Santa Cruz. Becoming acquainted with the community and supporting the launch of a swimming and sailing school was an opportunity for us to understand the Galapagos residents, their culture, struggles, and achievements.

Seahawk arrived in San Cristobal at the end of June of 2021. After a few days settling in from our latest crossing, we commenced work with our partner, YachtAid Global, to complete Galapagos’s first swimming and sailing community center, a Project 12 months in the planning.

YachtAid Global (YAG), a charity supported by a core group of yacht owners dedicated to working with ocean-bordered communities to enhance infrastructure, education, and environmental conservation, has been involved in several projects in the Galapagos with the intention to support the local population in areas where assistance is needed. Providing clean water systems to island schools, opening a new library, and delivering classroom supplies and computers nicely captures the nature of the organization’s efforts during its 16-year history.

The goal of this new project was the launch of Lobo Marino, a sailing and swimming school located in Bahia Naufragio, in San Cristobal Island, as well as the expansion of the swimming program to the islands of Isabella and Santa Cruz. The school focuses on a younger generation of Galapagos residents aged 10 to 17.

The program was born to address a need for certain life-saving skills including the ability to swim. According to the WHO and local authorities, 65% of children in the Galapagos don’t know how to swim. And by another estimate, 8,000 resident children do not have access to a facility that would allow them to master swimming.

For the population in Galapagos, the ocean plays a large role in people’s lives. Without the necessary swimming skills, children and adults are at risk of drowning. This is a problem that today accounts for 320,000 deaths a year around the world, particularly in low and middle-income countries.

The objective of the sailing program is to introduce children to a new sport that not only promotes physical fitness and self-confidence, but also fosters the creation of interpersonal bonds within the community. The exposure to boats and sailing also suggests opportunities to achieve a seafaring career both within the Galapagos and beyond.

Promotion of the initiative was also an important focus. Over the course of the two-week period, owners, crew, and YAG representatives worked to roll out the project with formal presentations to the community members, local authorities, and dignitaries. Most rewarding were the visits with island children, as many were excited to learn more about the new program.

The project started with the inauguration ceremony of the school that was conducted in the Malecón of San Cristobal. The program was presented to the local community, and agreements between YAG and the Municipality were signed. Following speeches from Seahawk’s team, as well as from local sailors that talked about their experiences, the presentation of the trophy for the annual sailing regatta was conducted.

News of our visit and the sailing school activities spread further up political echelons, and reached the Prime Minister of the Galapagos, who in fact joined us for dinner on board Seahawk. This was an interesting meeting, one suggesting the “Swim & Sail” had the attention and in most cases support of island leadership.

The following days were about spending time with the children on board Seahawk, introducing them to the discipline of navigating a large vessel and what it takes to be a professional crew member. We took the children and their parents sailing and showed them what living on a boat is like, along with the benefits of a vocation in seafaring.

The time spent by the crew teaching the kids how to sail was remarkable. On the islands of Isabella and Santa Cruz, Seahawk’s professional sailors gave the kids sailing lessons on Seahawk’s Tiwals, introducing them to a new hobby that many enjoyed and seem motivated to keep trying.

In support of the sailing program in San Cristobal, we got to know Emilio, a 15-year-old who previously had the fortunate experience to join another superyacht for a crossing from Galapagos to Tahiti. He is an extremely positive boy and was able to express his experience to the gathered children from the town at the presentations about the sailing school. He may well follow the path to a career at sea having been exposed to it at a young age, which is exactly what the school hopes to achieve with others in the community.

In San Cristobal, Seahawk provided the school with 4 new Optimist boats that were launched on the week of the inauguration, and the first lessons were conducted. Seahawk provided funding for the development of the facilities and the hiring of local sailing and swimming instructors.

The Swim & Sail project has been, without a doubt, one of Seahawk’s most rewarding projects. It was a fantastic opportunity for the crew and owners to engage with the Galapagos community.

The reception we received from the Mayors of the 3 main population centers, San Cristobal, Isabella & Santa Cruz, was amazing. The interest shown by the young people involved in the program was heartwarming. It is clearly apparent that the local community considers youth education important. Despite limited resources, they have built many recreational facilities, even though quality education is a challenge in some parts.

It is inspiring to see how Galapagueños take pride in their region, their land and their culture, as it’s shown by their commitment to making their archipelago home a better place. In particular, the focus on motivating youth to embrace understanding and preservation of the environment, their precious land, is heartwarming.

To this day we monitor project developments. Swim & Sail continues to grow, largely due to the hard work invested by YachtAid Global, other yachts, and so many local volunteers.

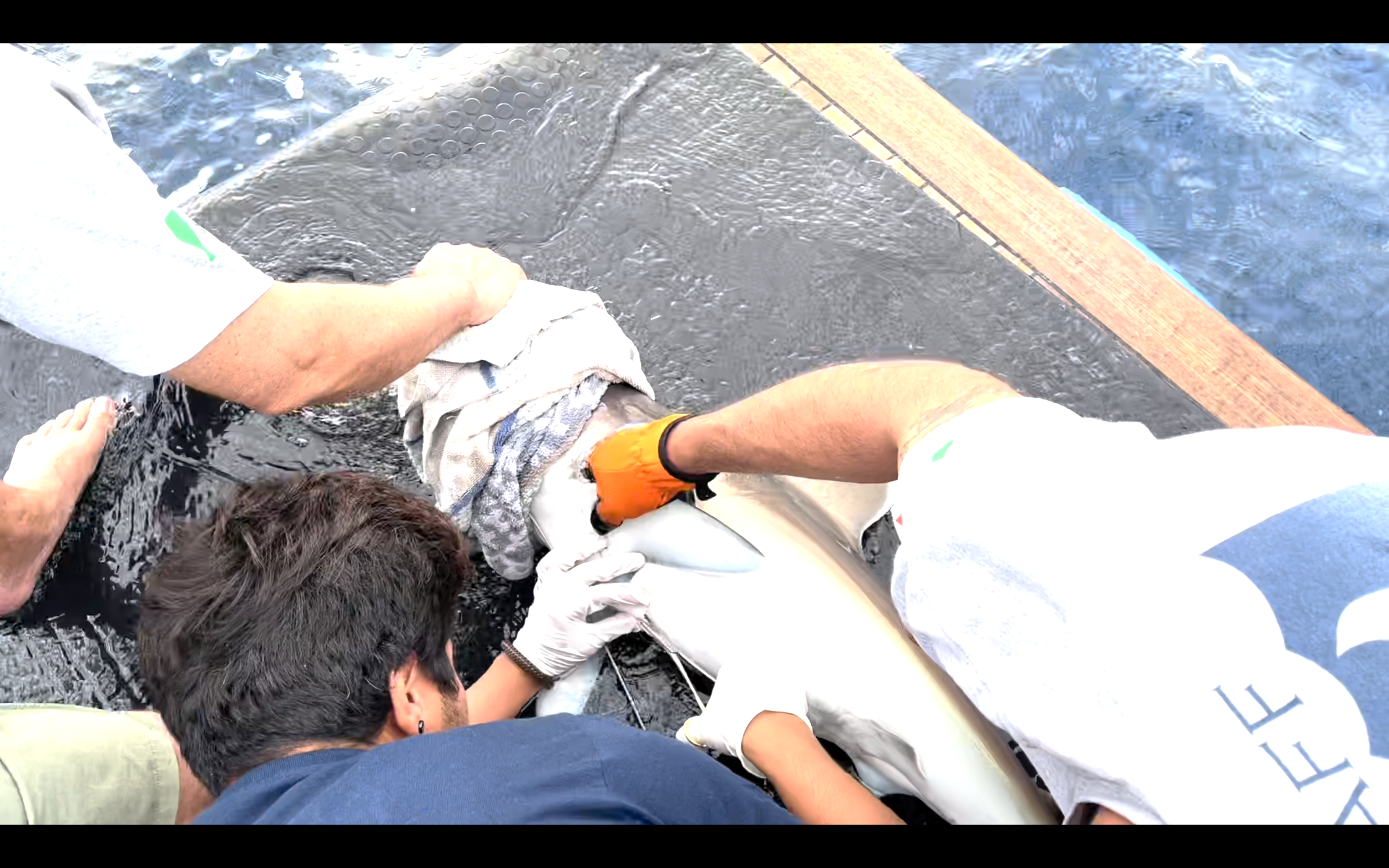

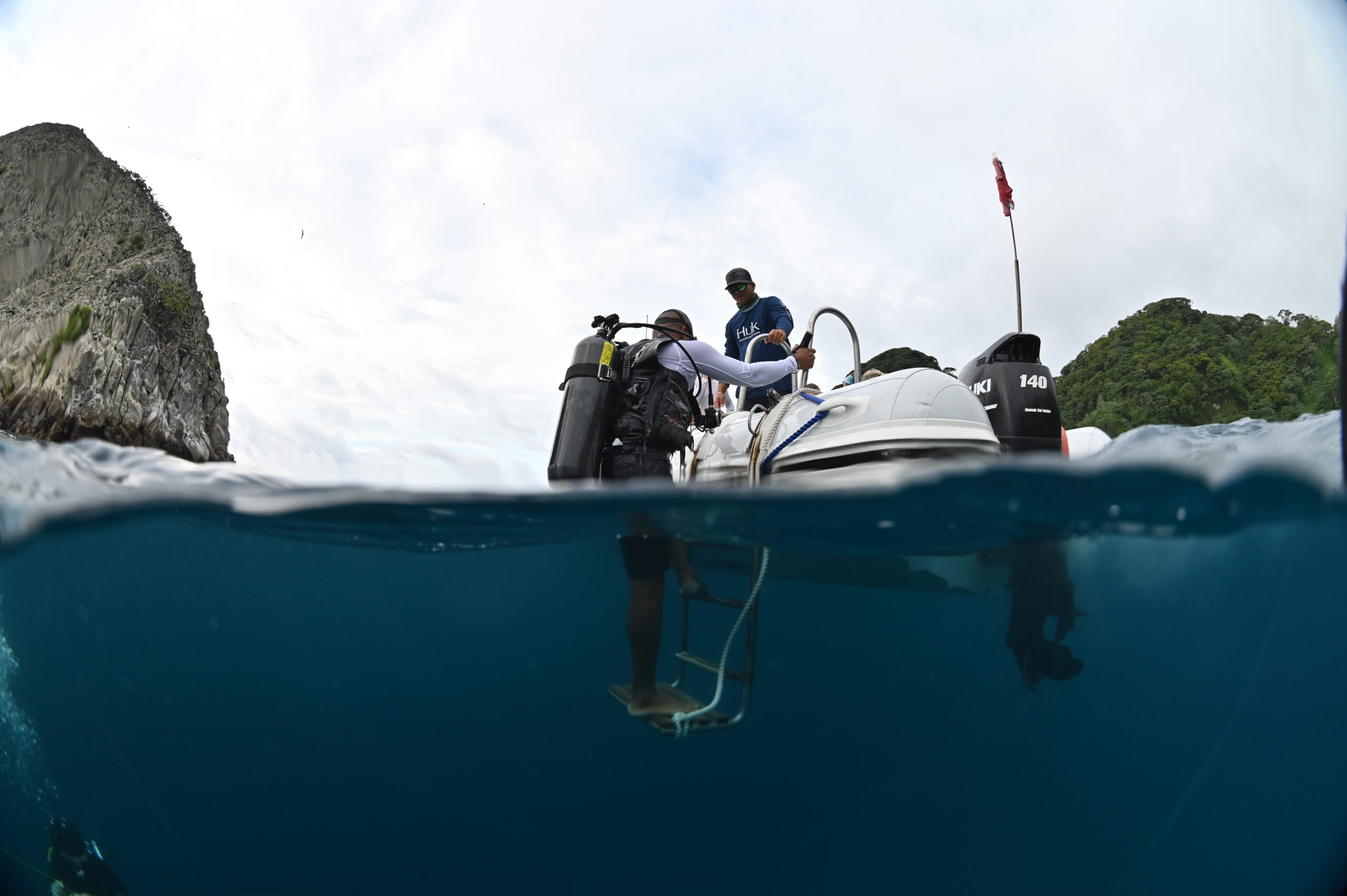

Next in Galapagos, Seahawk joins scientist Alex Hearn, one of the most respected and accomplished shark researchers in the world. The boat’s mission, Operation Swimway is an important shark migration study organized by Alex and his team with support from S/Y Seahawk. The work is to be conducted around the waters of Wolf and Darwin, remote islands located in the Northern Galapagos region. More to come on that soon.