Cocos island, as described by Jacques Cousteau to be the most beautiful island in the world, was a wild adventure for those on board during the 5 days we spent in the region. 300 NM from the nearest coast, Seahawk arrived after navigating for two days from its last position in Costa Rica.

The island looked as breathtaking as all the stories it inspired over the years said. The deep green of the vast tropical forest contrasted against the hundreds of waterfalls cascading off cliffs all around the island, making it look as if it was bleeding out, only to be covered by the heavy rains that keep this magnificent ecosystem flowing.

Located in the eastern tropical Pacific, Cocos National Park could appear to the eye as an island in the middle of the ocean, like an oasis in the middle of a desert. But Cocos is just the tip of an iceberg in a region surrounded by seamounts and connected by underwater ridges and ocean currents to other biodiverse regions such as the Galapagos and Malpelo.

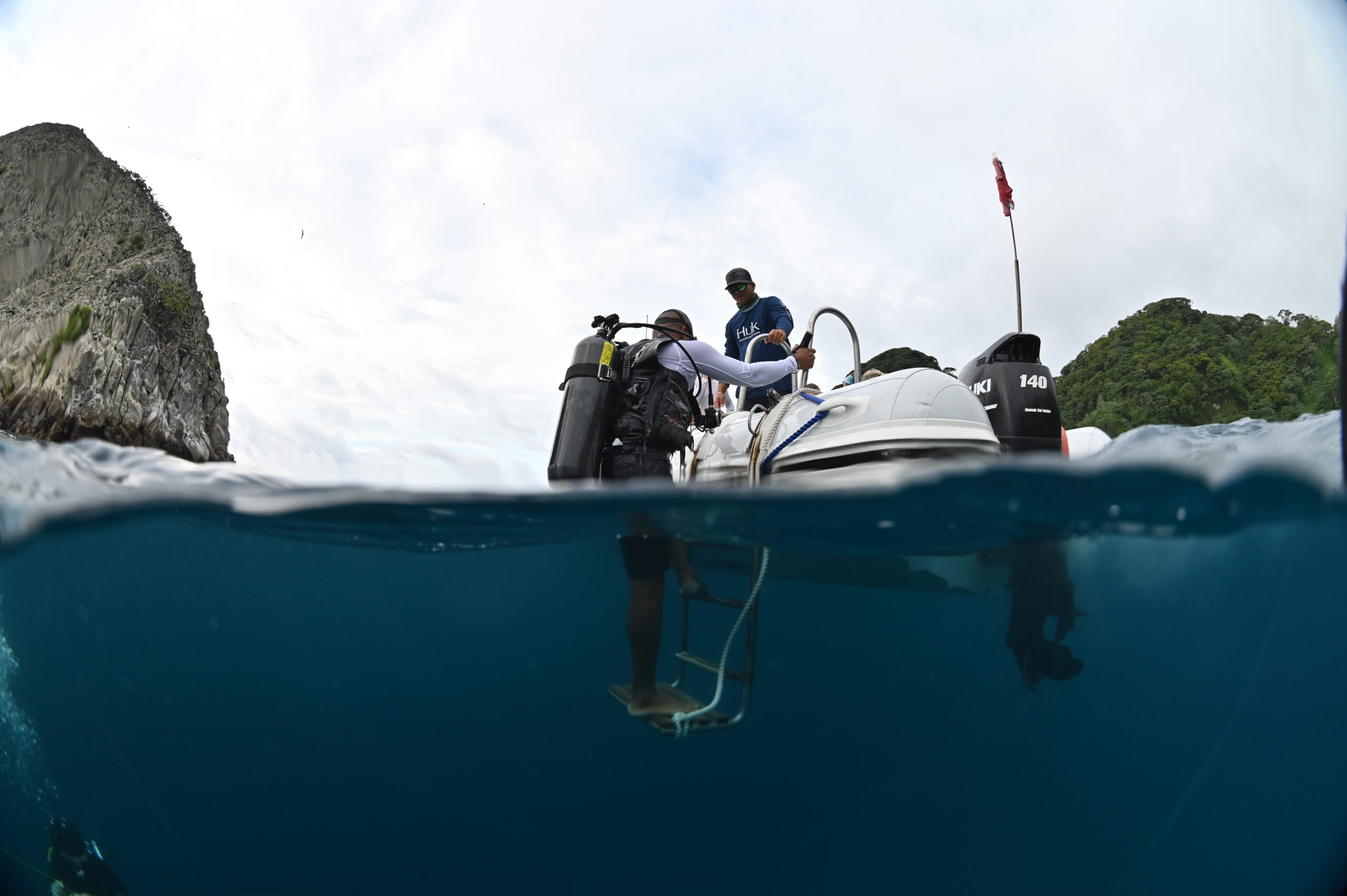

One thing was clear when we arrived in Cocos: we knew that it was a unique place, a place one doesn’t get the opportunity to go to often. The remoteness of the area and the permits needed make it inaccessible for most people. So taking advantage of our short time there, we conducted 3 dives each day along with multiple visits to the island’s shoreline and interior; a full power effort indeed.

Guiding us on this adventure we had Roberto Cubero. Roberto was a park ranger at Cocos years ago, spending months at a time living on the island and getting to know every corner of it. Now a local guide for Cocos and owner of his own dive shop, he welcomed us to his former station, taught us about the history of the island (one that includes pirates and hidden treasures), and took care of us on the many dives we did there.

Cocos is not for the faint-hearted. The currents that make this region thrive with all kinds of marine life also portend a wild and sometimes hostile environment for divers.

All dives in Cocos follow the same principle; everyone enters the water simultaneously, descending to the bottom as fast as possible. The concern is that the strong current at the surface risks the possibility of divers getting swept away into the open ocean.

Among Seahawk’s crew and owners, there are plenty of anecdotes about fighting currents and holding on to rocks at the bottom to avoid drifting away from the group. All added to the adventure, an adrenaline rush is enjoyed while diving among an abundant population of sharks (galapagos, silky, hammerheads, and others), huge schools of jacks and other species, with the spectacular topography formed by pinnacles, seamounts, and coral colonies serving as a backdrop.

The dive site called Dirty Rock is among the most rewarding and exciting. Named after all the guano that it’s covered in, Dirty Rock is one of the popular dive sites in Cocos, notorious for the school of scalloped hammerheads, thousands of jackfish, and a cleaning station where you can see many of the big fish engage with smaller ones for parasite removal. Here, the currents are very strong. And because the rock itself is only about 35 meters in diameter at the surface, successfully reaching a handhold at the bottom can be a real challenge, as being swept past the vertical walls that extend from the up-current side is a real possibility.

We definitely had some cortisol-producing experiences, as the one described by Seahawk owners, on one particular day that they remember very well:

“Only once during our time in Cocos did I feel truly threatened. Like many Cocos dives, this one had the group drifting some distance from the drop-in point, rendezvous with the tender prearranged. Unfortunately, the coordinates given to the driver were wrong, so upon surfacing there was no boat to collect us, just open sea, and our many predator friends below.

Diving with apex predators including some shark species suggests a degree of risk. But should these animals be feared? it depends. Statistically, there are very few examples of sharks attacking humans, and even fewer cases involving divers. And applying mitigations like restricting dives to daylight can help. Observing near cleaning stations where parasite-eating Barberfish tend to calm the animal is also a good idea. Still, attacks involving divers, although rare, can occur, as in the case of one particularly grumpy Cocos resident tiger shark aptly named La Gorda (the Fat one). She was involved in a fatal accident with a visiting Cocos diver only a few years prior to our visit.

Swimming on the surface, even if practical, is a scary proposition in shark-laden waters. The sounds/images produced suggest prey to the sharks. Crinkling sounds like those made with an empty plastic water bottle being crushed are especially worrisome. Dying fish produce something similar. And keep in mind that sharks do not see that well. Shark attacks usually happen by mistake.

What really worried me though was our guide Roberto’s reaction to the tender being missing. “This is bad, very bad!” he said. “Where’s the boat?” If he is scared, perhaps I should be, too? The good news: it was day and the seas were relatively calm. Happily, both land and the yacht were in sight although quite far away. Theoretically, we could swim to the yacht or to shore. But the swim would be long, and likely provocative, an invitation for those lurking below. What to do?

Some divers including Roberto had reserve air. He immediately descended slightly below the group to keep guard while the rest of us bobbed quietly on the surface. For those with air remaining, the plan was to take turns guarding from below, one at a time until everyone’s air was exhausted hoping the tender would return in time.

The tender did eventually find us, and in reality, the wait was no longer than about 25 minutes, albeit a long 25 minutes.

The missing tender experience reminds me that even well-intentioned circumstances can turn quite desperate due to the smallest error or just plain bad luck. That swim would have been very exciting. Had it been night, out of sight of land in rough seas, lost, the outlook would have been grim. A cautionary tale for those wishing to explore the magnificent underwater world exemplified by Cocos. Be careful and consider carrying an emergency locator/transmitter as we now do on all Seahawk dives.”

Among the many highlights of our expedition to Cocos, there’s an encounter with a particularly large and very active bait ball. From a distance, the water was seemingly boiling with life (and death as it turns out). as we approached, we saw dozens of dolphins hunting for prey while seabirds attacked from above, all engaged in what only can be described as a feeding frenzy. Of course, it made perfect sense to jump in with masks and snorkels to join the unfolding underwater chaos.

What a wild experience to be a spectator of one of nature’s most fascinating phenomena. Being surrounded by dolphins while large fish congregations swam around us was fascinating, at least until it was observed that among the dolphins there were several large sharks engaged in the fray. At that moment we realized that watching should probably enjoy a lower priority than survival. In general, it isn’t a good idea to be in between the predator and prey. Needless to say, no one has ever climbed back into the tender as fast as we did that day.

On land, Cocos has a wealth of pleasing surprises to reveal. The many waterfalls, the tropical lushness, and the vast biodiversity of terrestrial species make Cocos a paradise we were lucky to explore. And this is not a typical walk in the park. Accessing the most beautiful stops requires a fair amount of agility and definitely no fear of heights. One of the spectacular waterfalls, for example, requires the visitor to climb up a two-story make-shift and rickety ladder to reach a lagoon tucked away in between the dense island vegetation.

Cocos history is also very interesting. The past is complete with a legacy of piracy and treasure hunters, some of whom have left markings on the large boulders that line the island’s few beaches. Is there treasure to be found? None so far, despite the crew’s effort to make sense of the clues. Perhaps the story is more about vanity, as the names of old vessels were carved into the rocks by seafarers across history wanting to leave their mark.

Our Cocos adventure marked the beginning of a journey to explore the world’s most incredible underwater destinations. Seahawk continued on to the Galapagos and the Revillagigedo archipelago later on, both overwhelmingly fascinating places to see incredible marine life. Yet, to this day, the magic of Cocos lives uniquely in our collective memory as a treasure, both wild and beautiful, a place to be rejoiced and preserved.

This beginning was also a turning point in the way many of us saw the ocean. As we engaged with so many of the species we saw in Cocos, we learned about the threatened status of many of them, like the endangered scalloped hammerhead shark. And unfortunately, even though the Marine Protected Area is heavily guarded by the Costa Rican government, Cocos is as vulnerable to the increasing threats of climate change, as well as the overfishing that happens just outside of it.

Because of this, efforts to protect the Cocos-Galapagos Swimway that many of these animals use on their long migrations are critical for the species’ survival. With the protected corridor now supported by Ecuador, Colombia, Panama and Costa Rica, many of these fishing pressures could drop and allow some species to recover. Still, there is a lot of work to do in the battle against overfishing.

Isla del Coco was an unforgettable expedition, and as we continue our trip into the Pacific in search of new adventures, there is an idea that lingers in the air. That maybe, one day, we will be back.

Much to celebrate, much to anticipate as we make our way around the world.