Seahawk wins 2023 YCM Explorer Award

Last month, S/Y Seahawk received the 2023 YCM Explorer Awards by La Belle Class Superyachts for Adventure and Environmental Ethics. These awards recognize Superyacht owners with a commitment to marine conservation and sustainability, shown in areas such as innovative technology on board or philanthropic programs.

The awards are given by a jury of experts in the areas of Technology & Innovation, Mediation & Science, Adventure & Environmental Ethics

Rotational Chief Stewardess Nicola Watton received the award on behalf of S/Y Seahawk’s owners and crew. The award was presented by Prince Albert II of Monaco at the Yacht Club de Monaco.

S/Y Seahawk’s team is proud of the work done in the past three years, and looking forward to supporting new projects in the future, wherever in the world we are.

With this recognition, we hope to inspire other Superyacht owners to turn their adventures at sea into philanthropic programs that help local communities and support scientific research, key to protecting our marine environment.

From the Jury:

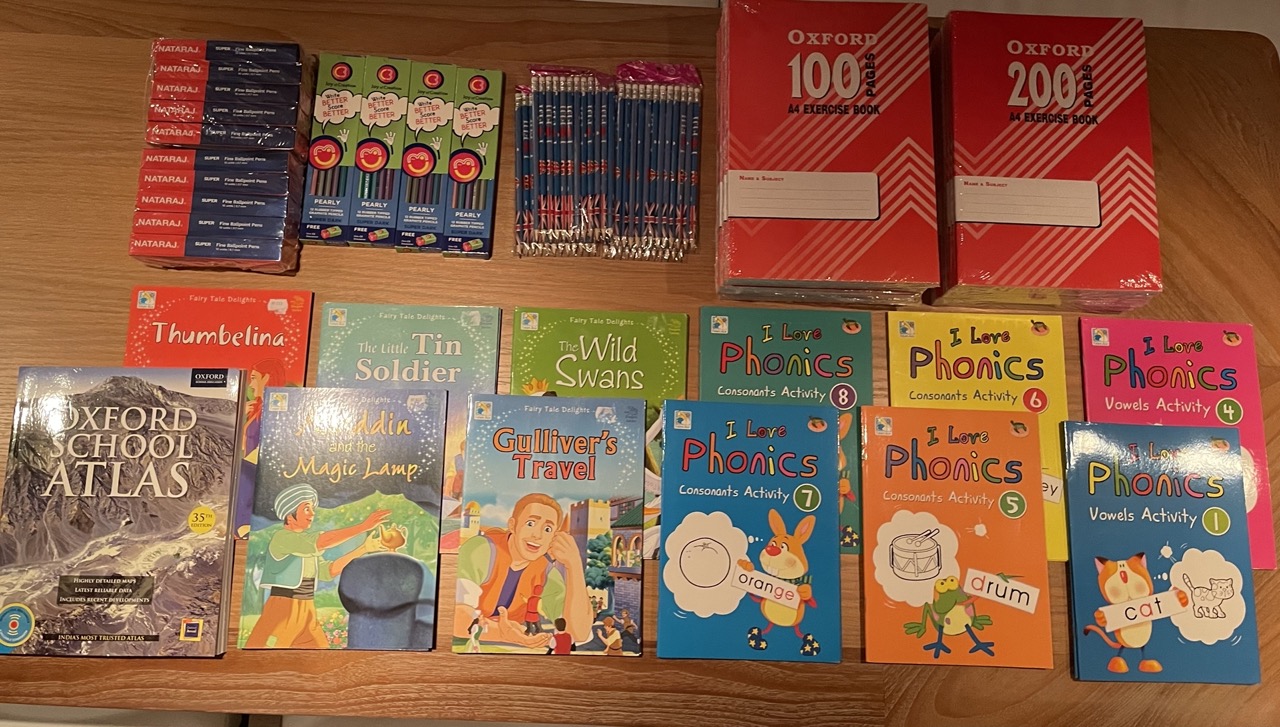

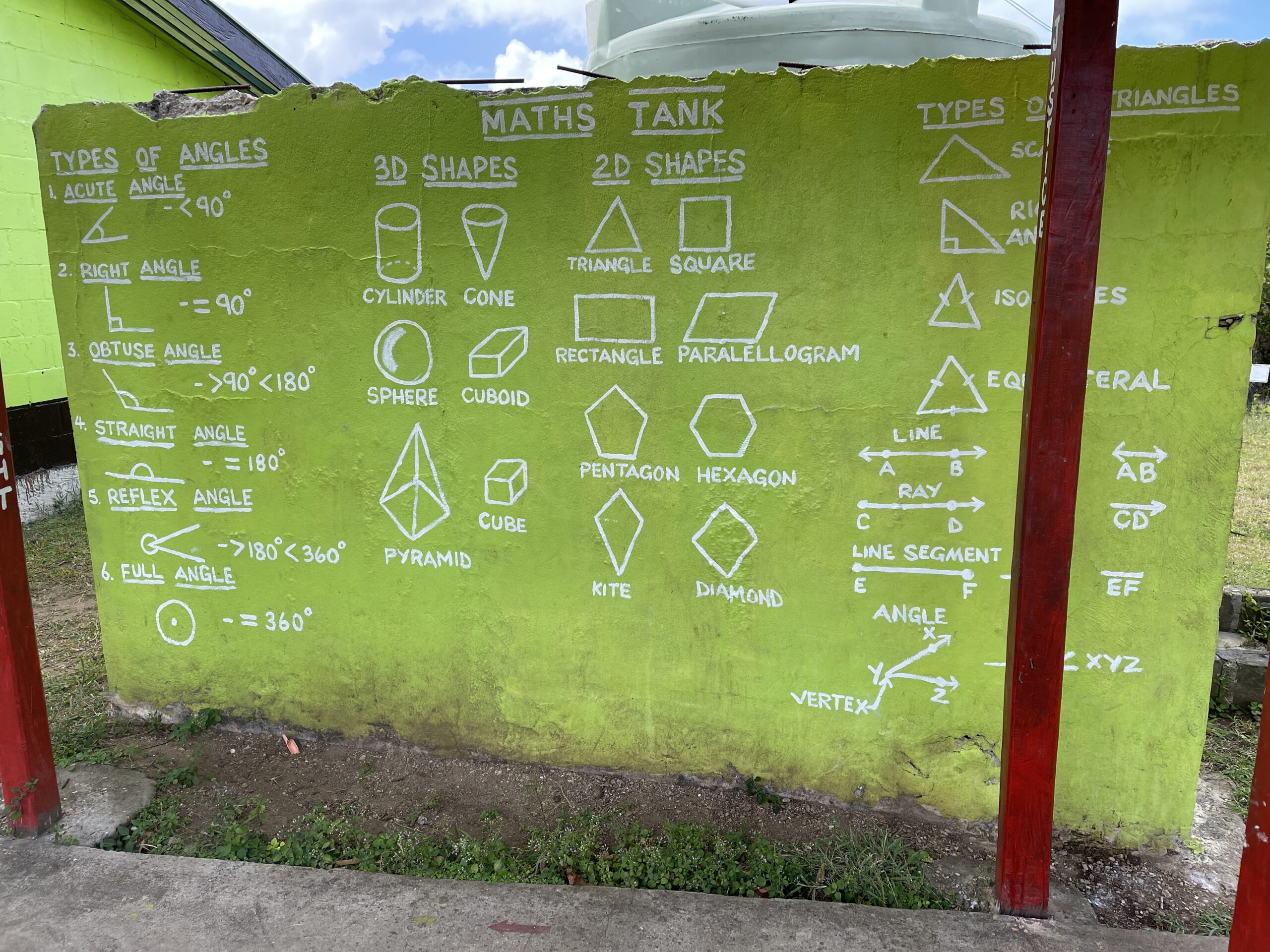

“S/Y Seahawk (60m) was presented as a yacht not built for science but with a strong desire to help science and the oceans. It has carried out numerous missions that have helped better understand migration patterns, fishing impact, etc. The yacht is also associated with projects such as the set-up of a sailing school in the Galapagos Islands with Yacht Aid Global, funding an instructor and converting a building for the school. It has also supplied educational materials to schools in the Tuamotus (French Polynesia) & Fiji archipelagos in 2022; all of which won it the award in the Adventure & Environmental Ethics.”

All images are courtesy of Yacht Club de Monaco | Mesi

You can read the full article about the Explorer awards here.